The Bengal School of Art, also known as the Bengal Renaissance, emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as a revolutionary force in Indian art. Led by visionary artists such as Abanindranath Tagore and Nandalal Bose, the movement sought to revive and redefine Indian art amidst the overwhelming influence of Western styles. This school played a pivotal role not only in the Indian Independence art movement but also in influencing literature, music, and theatre.

The genesis of the Bengal School can be traced to a reaction against the colonial aesthetic that had dominated Indian art for decades. During the British Raj, traditional Indian painting styles were overshadowed by the Western techniques introduced by British artists and collectors. Known as ‘Company Paintings’, these works were characterized by their documentary nature, depicting India’s flora, fauna, and daily life in a style palatable to British tastes [1].

A significant shift occurred when Ernest Binfield Havell, the Principal of the Government College of Art in Calcutta, began advocating for a return to Indian artistic traditions. Havell, along with Abanindranath Tagore, championed the Mughal miniature style, which they believed captured the spiritual essence of India, as opposed to the materialism of the West [2].

Abanindranath Tagore, often regarded as the founder of the Bengal School, was instrumental in this renaissance. He was also the principal artist and creator of the Indian Society of Oriental Art, which he founded along with his brother Gaganendranath Tagore in 1907 to promote awareness of India’s rich artistic heritage [2]. This journal became a platform for intellectual exchange and cultural pride. Tagore was the first major exponent of Swadeshi values in Indian art, and his influential work led to the development of modern Indian painting [1].

His iconic painting ‘Bharat Mata’ (Mother India) depicted a young woman symbolizing India’s national aspirations, embodying the movement’s nationalist spirit. Tagore’s works often drew inspiration from Indian mythology, folklore, and nature, blending indigenous styles with elements of Japanese and Chinese art, and emphasizing the use of natural pigments [2].

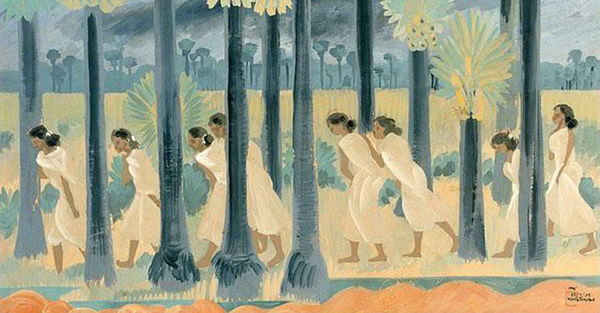

Nandalal Bose, a student of Abanindranath, furthered the movement by mentoring young artists and incorporating themes from Indian mythology and rural life into his work. His painting ‘Sati’ exemplifies the delicate yet powerful style characteristic of the Bengal School. Bose’s dedication to teaching at institutions like Visva-Bharati University ensured the perpetuation of the school’s ideals [1].

Despite its initial success, the Bengal School began to decline in the 1920s with the rise of modernist ideas. However, its legacy endured, laying the groundwork for modern Indian art. The movement’s emphasis on indigenous techniques and themes inspired subsequent generations of artists to seek a distinct Indian identity in their work [2].

Today, institutions like the Government College of Art and Craft in Kolkata and Visva-Bharati University continue to train students in the traditional styles of tempera and wash painting, preserving the legacy of this seminal period in Indian art history. The Bengal School of Art remains a testament to the power of cultural resurgence and the enduring impact of artistic nationalism [1].

References

1. Guha-Thakurta, T. (1992). The Making of a New ‘Indian’ Art: Artists, Aesthetics, and Nationalism in Bengal, c. 1850-1920. Cambridge University Press.

2. Mitter, P. (1994). Art and Nationalism in Colonial India, 1850-1922: Occidental Orientations. Cambridge University Press.