In the 1980s, a new artistic wave swept across India, signalling a dramatic shift from the abstraction and modernist aesthetics that had dominated the country’s art scene in the preceding decades. This movement, known as Narrative Figuration, reintroduced figuration into contemporary Indian art, setting the stage for a period of intense creative exploration that would blend tradition with modernity. Emerging against a backdrop of political upheaval, globalization, and rapid urbanization, Narrative Figuration was not merely a reaction to Western modernism; it was an engagement with the cultural, social, and political landscape of India at a pivotal moment in its history.

But by the 1980s, a growing sense of disillusionment with the elitism of abstract art led many artists to seek a return to storytelling and figuration. They believed that art should not only engage with form and aesthetics but also provoke emotional and intellectual responses by drawing from the everyday realities of Indian life. This period saw artists turning to India’s rich traditions of mythology, folklore, and religious epics, merging these ancient narratives with contemporary political concerns. What emerged was a powerful synthesis of cultural symbols and modern relevance, reflecting the complexities of gender, class, caste, and urban existence.

Figuration was seen by artists of this movement as a crucial and accessible language for conveying these themes. It allowed for a kind of narrative storytelling that abstraction had often overlooked. Through figuration, artists could depict not just human forms but the nuanced stories of people’s lives—stories that resonated with the societal changes taking place. These works often tackled issues such as migration, urban poverty, gender violence, and political instability, mirroring India’s transition into the late 20th century.

Nalini Malani, a prominent figure in this movement, was one of its most influential artists. Born in Karachi in 1946, Malani’s work was shaped by the partition of India and the displacement of millions. Her art sought to engage with the marginalization of women and the violence they experienced. Using a wide array of media, including painting, video, and installation, Malani created intricate narratives that wove together Indian mythology with contemporary feminist concerns. Her 1980s works like “Tales Retold” served as both personal and political commentary, reinterpreting mythological tales to challenge historical representations of women and expose the hypocrisies embedded in Indian society.

Sudhir Patwardhan was another leading artist of this period, known for his depictions of urban life. Born in Pune in 1949, Patwardhan became a key figure in representing the lives of ordinary people caught in the rapidly modernizing landscape of India. His paintings, such as “Mumbai Landscape” (1981), are steeped in social realism, capturing the resilience and dignity of laborers, migrants, and slum dwellers. His commitment to figuration provided a voice to the marginalized, portraying the harsh realities of urbanization without romanticizing the struggle.

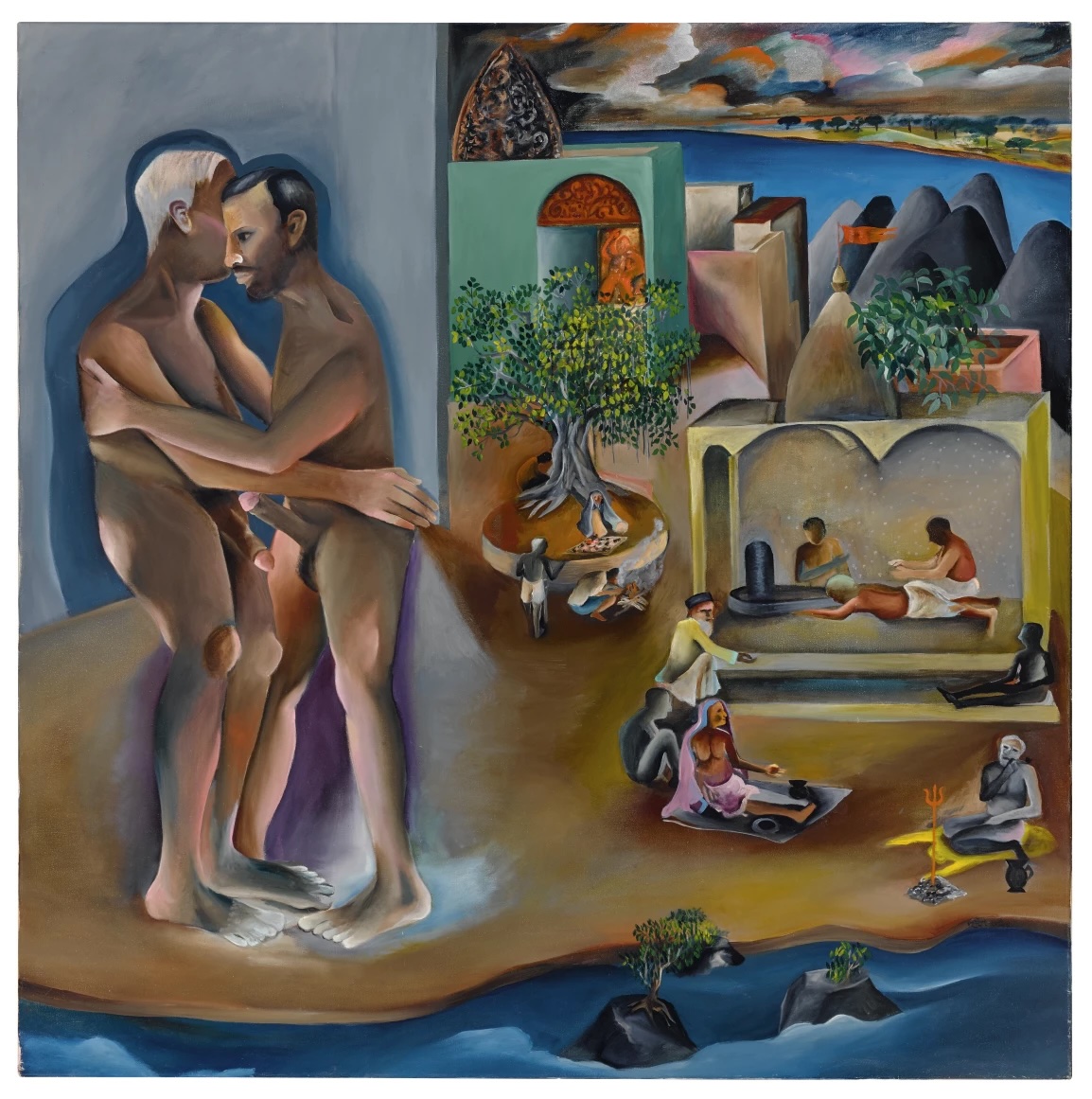

Bhupen Khakhar, emerging as one of the most distinctive voices within the movement, Born in 1934 in Bombay, Khakhar’s work combined narrative figuration with humor, irony, and a deeply personal exploration of identity. As one of India’s first openly gay artists, his works often reflected the complexities of living a marginalized life in a conservative society. Paintings like “Man with a Bouquet of Plastic Flowers” (1976) revealed his own experiences of sexuality while simultaneously offering a broader commentary on the intersection of personal and social identities. His compositions drew from both high art and popular culture, blending Indian street life with religious iconography to reflect on human relationships and societal norms.

The aesthetic of Narrative Figuration was marked by a vibrant return to figurative compositions, but these figures were not merely portraits or symbols of individual identity. Rather, they were imbued with narrative potential, their dramatic gestures and expressions set against backdrops rich with cultural and religious symbolism. Artists borrowed from traditional Indian art forms—such as miniatures, murals, and folk art—while incorporating contemporary themes, creating a unique visual language that resonated deeply with Indian audiences.

The use of color in these works also stood out. Drawing from India’s diverse artistic heritage, many artists employed bold, expressive palettes that evoked the vibrancy of popular Indian art forms. These vivid colors, combined with a strong narrative focus, helped bridge the gap between abstract modernism and the storytelling traditions that had long been central to Indian culture.

By the early 1990s, however, the momentum of Narrative Figuration began to wane as new global art trends, such as postmodernism and conceptual art, gained prominence. The rise of digital media also shifted the focus away from traditional figuration. Nonetheless, the impact of this movement on Indian contemporary art was deep. It had opened up new avenues for artistic expression, allowing for a more direct engagement with pressing social and political issues through the lens of figuration and narrative.

Artists like Nalini Malani, Sudhir Patwardhan, and Bhupen Khakhar left an indelible mark on the Indian art world, influencing a new generation of artists who continued to explore figuration and storytelling in their work. Although the movement itself began to decline by the early 1990s, its legacy persisted. The groundwork it laid for engaging with themes of identity, gender, class, and politics continued to shape the broader art scene in India, well into the 21st century.

The emergence of Narrative Figuration during the 1980s was a reminder of the role that art can play in reflecting and challenging the social, political, and cultural realities of its time. It reintroduced the human figure as a vehicle for storytelling, creating works that were not only visually compelling but also rich with narrative meaning. This movement helped bridge the gap between abstraction and narrative art, combining the deep-rooted traditions of Indian culture with the urgent questions of modern life.