After World War I, a wave of artistic movements emerged, seeking new directions to express the profound societal changes. In Germany, the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) emerged in the 1920s as a reaction against the emotional expressionism and abstraction that dominated the pre-war years. This movement, first named by art historian and museum director Gustav Friedrich Hartlaub for a 1925 exhibition, aimed to depict the world with clarity, precision, and a focus on social and economic realities, offering a more objective and realistic portrayal of the world.

On June 14, 1925, Hartlaub curated an exhibition at the Kunsthalle Mannheim titled Neue Sachlichkeit: Deutsche Malerei seit dem Expressionismus (New Objectivity: German Painting Since Expressionism). The result of two years’ research, the exhibition displayed the works of artists who had turned away from Expressionism in favor of a ‘new naturalism’ that Hartlaub called New Objectivity.

New Objectivity, as defined by Hartlaub, comprised two stylistic tendencies:

I see a right and a left wing. The first, so conservative as to be equal to Classicism, rooted in that which is timeless, is seeking once again to sanctify that which is healthy, corporeal, sculptural, through pure drawing from nature… The other wing, incandescently contemporary in its lack of belief in art, born rather from a denial of art, is attempting to expose chaos, the true feeling of our days, by means of a primitive obsession with assessment, a nervous obsession with the exposure of the self.

The exhibition included 124 works by artists such as Georg Schrimpf and Alexander Kanoldt (of the “right” or neo-Classicist wing) and George Grosz and Otto Dix (of the “left” or Verist wing). The exhibition, which traveled to several other German cities, was a popular and critical success and helped popularize the New Objectivity style.

Expressionism, with its emphasis on individual emotions and distortions of reality, lost resonance in the face of post-war anxieties and disillusionment. In contrast, the New Objectivity sought a clear-eyed and critical examination of the social and political realities of the Weimar Republic (1919–1933). Artists turned their attention to the everyday lives of people, particularly those living in rapidly growing cities, aiming to capture the essence of the contemporary experience with an unflinching and realistic approach.

New Objectivity in painting was characterized by an unsentimental, precise representation of reality, often focusing on still lifes and portraits. Artists like Christian Schad, Conrad Felixmüller, and Ernst Thoms depicted subjects with a stark, almost clinical precision. Their works avoided emotionalism, instead emphasizing clarity and detail to reflect the world as it was.

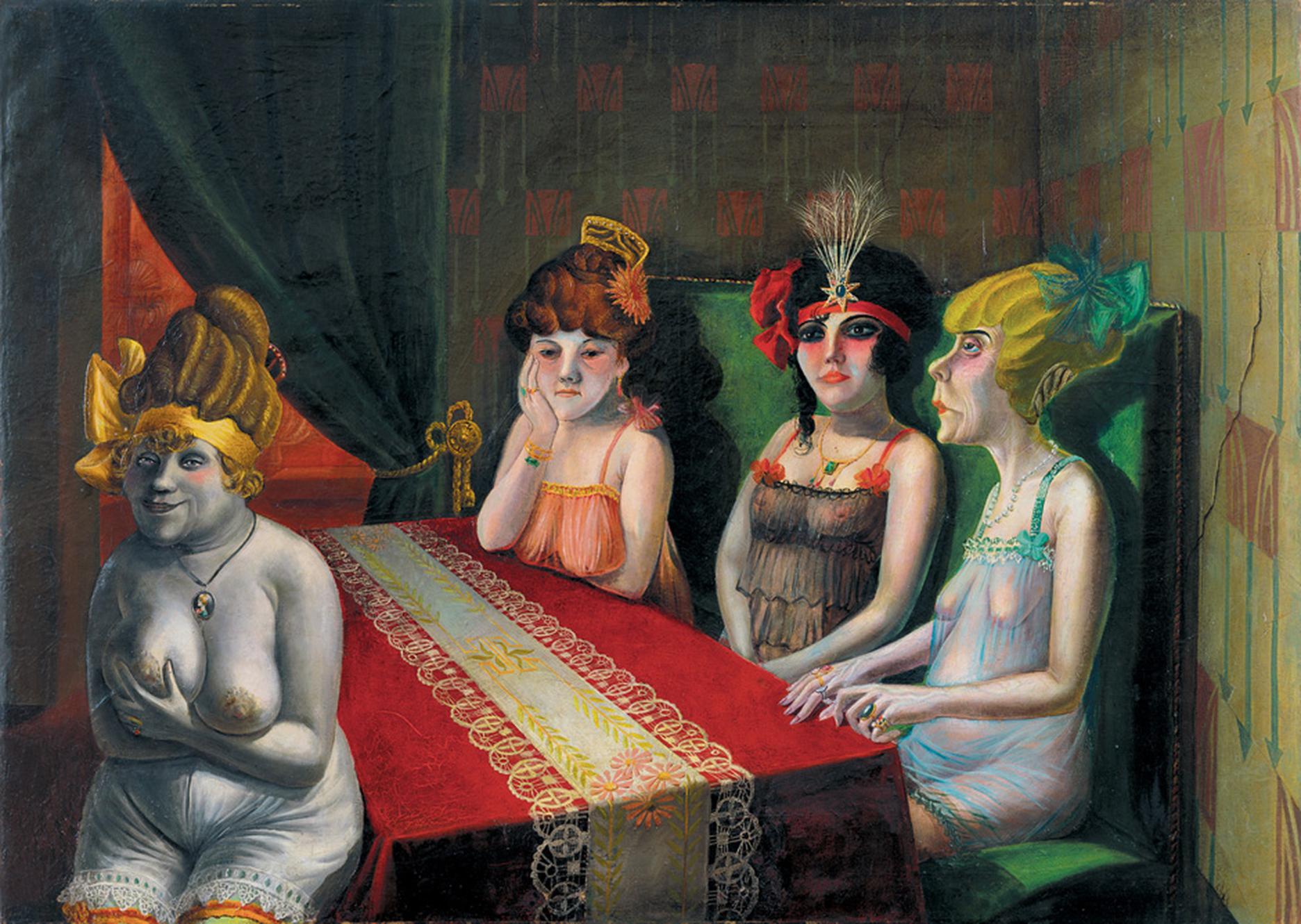

The movement had three main currents. The first was the politically charged, socially critical “veristic” wing, led by artists such as George Grosz and Otto Dix. Their works often highlighted the harsh realities and injustices of society, using sharp, realistic detail to critique the socio-political conditions of the time.

The second current was the classical, idealizing style represented by Georg Schrimpf and Alexander Kanoldt. This wing sought to return to timeless, traditional values, focusing on pure, naturalistic drawing from life. Their works often portrayed serene, balanced compositions that contrasted with the chaotic, fragmented reality of the post-war period.

The third current was Magical Realism, where artists like Max Beckmann blurred the lines between objective depiction and the fantastical. This approach combined realistic detail with dreamlike or surreal elements, creating works that were both grounded in reality and infused with imagination.

The New Objectivity stands as a fascinating and complex chapter in art history. It offered a compelling visual commentary on the turbulent times of the Weimar Republic, capturing the social tensions, political anxieties, and yearnings for a more stable future. By exploring the diverse styles and themes within the movement, we gain a deeper understanding of this pivotal period in German history.

Grosz, George ‘Drinnen und Draussen’ (Arm und Reich),

1926.