Jugendstil (Young Style) was an artistic movement that flourished between 1890 and 1910 in Germany. It was launched in the mid-1890s in Munich by Swiss-born artist Hermann Obrist, and the city soon became the early center of the movement, which included prominent figures such as August Endell, Bruno Paul, Bernhard Pankok, and Otto Eckmann.

The term “Jugendstil” comes from the magazine Die Jugend (The Youth), founded in Munich in 1896 by the writer G. Hirth. The magazine played a key role in promoting the movement’s ideas and lent its name to the artistic style. Jugendstil, like similar movements in other European countries—such as the Secessionist movement in Austria and the Glasgow Style in Scotland—was part of the broader Art Nouveau movement, each with its own unique characteristics and influences. Jugendstil aimed to move away from traditional academic art and instead embraced modern, decorative, and nature-inspired forms. The style often featured floral motifs, arabesques, and organically inspired lines, eventually evolving toward abstraction and functionalism.

Jugendstil arose as a reaction to the industrialization of Europe in the late 19th century, which led to significant technological and social transformations. Many artists and designers, disillusioned by the soulless, mass-produced goods of industrialization, sought to revive craftsmanship, emphasizing individuality and creativity in their work. The movement later evolved into a more abstract phase, influenced by the work of the Belgian-born architect and designer Henry van de Velde in Vienna. Jugendstil rejected the historicism and rigid academic styles of the 19th century. Instead, artists embraced flowing, organic lines and sought to harmonize art with nature, blending fine and applied arts in works that ranged from paintings and sculptures to furniture, architecture, textiles, jewelry, and graphic design.

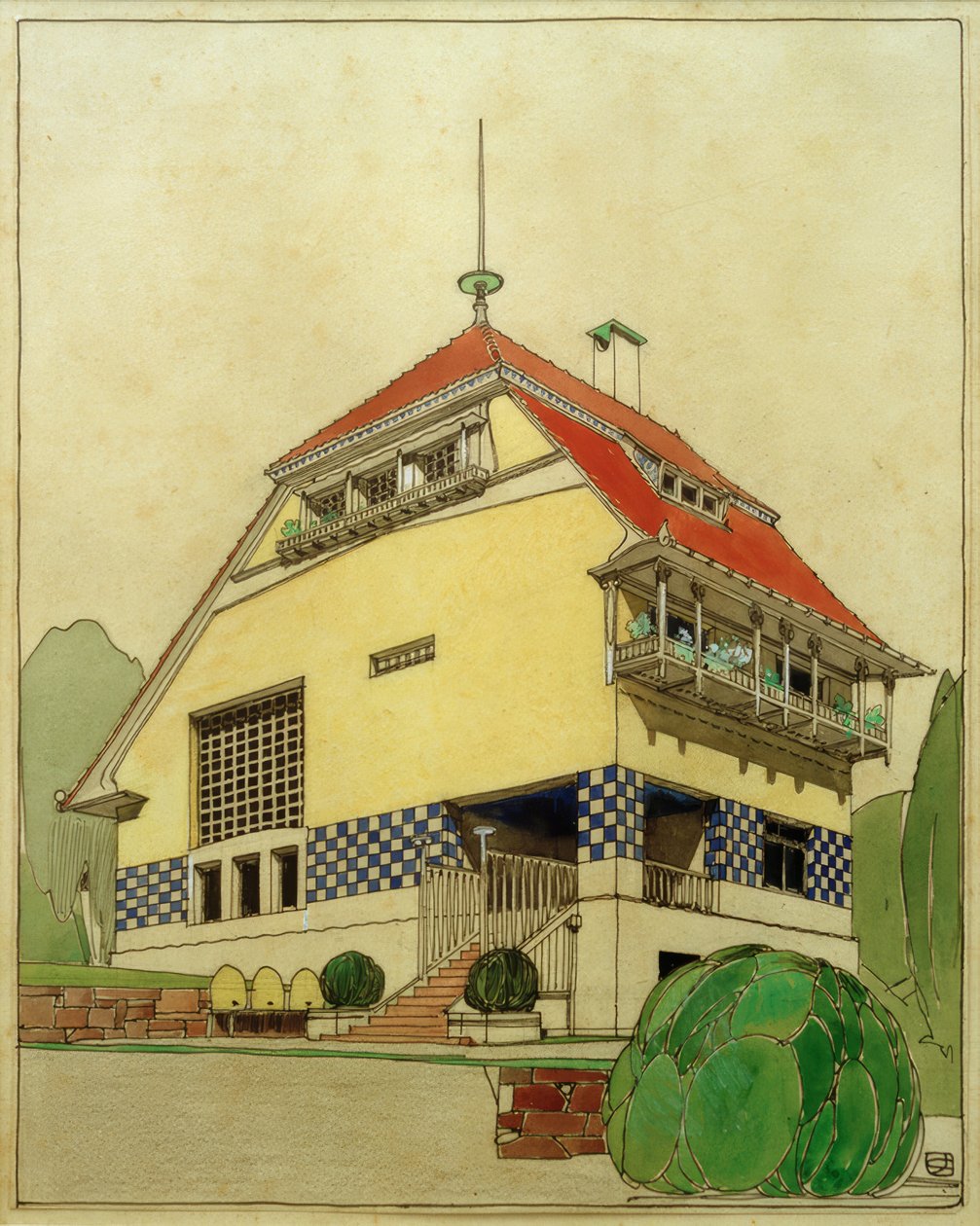

Jugendstil artists developed a distinct visual language that set them apart from traditional academic art. Their work was characterized by organic, flowing lines inspired by natural forms such as plants, flowers, and animals, which gave their designs a sense of movement and fluidity. These lines were often accompanied by rich ornamentation that was integrated into the structure of objects and buildings, becoming an essential part of the overall design. Nature-inspired motifs, including leaves, vines, flowers, and animals, were stylized and abstracted to create harmonious, balanced compositions.

The movement placed a high value on craftsmanship and the use of high-quality materials, in contrast to the mass-produced goods becoming more prevalent due to industrialization. Additionally, Jugendstil artists sought to synthesize various art forms, combining painting, sculpture, and architecture into unified, immersive designs. Even buildings were adorned with decorative elements that extended to furniture, stained glass, and lighting fixtures.

Several artists and designers played key roles in shaping the Jugendstil movement, contributing significantly to its development across different disciplines. Peter Behrens was a crucial figure in German Jugendstil, recognized for his work in architecture, painting, and graphic design, particularly in projects like the AEG Turbine Factory in Berlin. His contributions to industrial design and corporate branding for AEG (Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft) made him a pioneering modernist architect. Otto Eckmann, another influential figure, contributed to the movement through graphic design and typography, creating the iconic “Eckmann” typeface that became emblematic of the Jugendstil style. Hermann Obrist, a Swiss-German sculptor and designer, is remembered for his decorative work, especially his “whiplash” motif, which used curving lines to evoke the flowing rhythms of nature. Henry van de Velde, despite being Belgian, had a significant impact on Jugendstil in Germany by promoting the integration of form and function in design, emphasizing simplicity, functionality, and aesthetic harmony. He worked across interior design, furniture, and graphic arts.

Jugendstil made a substantial impact on architecture, fully realizing its principles of organic design and decorative integration. Architects like August Endell and Joseph Maria Olbrich exemplified these ideals in their buildings. Endell is particularly known for his highly decorative facades, such as that of the Elvira Studio in Munich (1897–98), which featured swirling, plant-like forms that made the building appear as though it had sprung from nature. Olbrich, a key figure in the Vienna Secession (closely related to Jugendstil), designed the Secession Building (1897) in Vienna, an iconic example of Art Nouveau architecture with its minimalist white façade and gilded dome of laurel leaves.

By the early 1910s, Jugendstil began to lose its momentum, giving way to the geometric simplicity and functionalism of modernist movements like the Bauhaus. The rise of industrial design and the demand for mass production during and after World War I also contributed to the movement’s decline. However, Jugendstil left a lasting legacy. Its emphasis on craftsmanship, design, and the integration of art into everyday life paved the way for modernist design principles. The movement’s focus on organic forms and natural motifs had a lasting influence on the development of decorative arts and design in the 20th century.